Future Work/Life is a weekly newsletter that casts a positive eye to the future. I bring you interesting stories and articles, analyse industry trends and offer tips on designing a better work/life. If you enjoy reading it, please share it!

There's a running theme in my newsletters, of which I'm well aware. I often paint a positive picture of the future of work, which is in stark contrast to the reality that many people experience in their day-to-day lives. For the young Goldman Sachs employees who recently got together to voice their concern at the effect of working demands on their health, this is certainly true. Likewise, their many colleagues suffering from burnout; three to six of whom per team in London are on sick leave at all times.

Although companies like Goldman Sachs have a reputation for grinding people down in exchange for substantial financial compensation and a significant career accelerant, the cause is rarely a malevolent group of people whose intention is to suck the life out of their employees. It's usually something much more straightforward - money or poor leadership.

Wellbeing is usually well down the list of priorities, which given the more than challenging economic circumstances over the past year, is, to some degree, understandable. After all, you could create the best culture in the world, but if your company goes out of business, it's a pointless exercise.

More commonly, though, despite most people within organisations professing to value the importance of wellbeing, they're either unable or unwilling to create an environment in which it can realistically succeed.

On the podcast last week, I spoke to Jennifer Moss, who has spent the majority of her career writing about the psychology of work and, in particular, happiness. However, over recent years, she has become a leading expert on burnout. Now, we've all heard of burnout, and the likelihood is you'll have read not just about its gradual increase before the pandemic but its explosion since.

[In fact, Jen's articles on the subject are among Harvard Business Review's most-read articles of the past year, so make sure you read them when you get a chance.]

So we're all on the same page about what burnout actually means; the World Health Organization defines it as:

"a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed."

The point here is that while it affects (far too many) individuals, its root is within the workplace, and, therefore, it's the responsibility of organisations to address it.

During our conversation, we discussed Christina Maslach, who has spent forty years studying the effects of burnout at work and breaks down the causes into six categories:

Unsustainable workload

Perceived lack of control

Insufficient rewards for effort

Lack of a supportive community

Lack of fairness

Mismatched values and skills

While there's no magic bullet solution to ‘fix’ burnout, I'd like to focus on a couple of observations and highlight a possible response to each.

Passion leads to burnout

Given the last of Maslach's causes of burnout relates to a lack of meaning or purpose in your job and that one of the manifestations of this is cynicism, it seems rather incongruous to conclude that passion leads to burnout. Yet, as Jen wrote in another article, some of the people most at risk are those who love their jobs and those in professions that demand high levels of empathy, such as doctors, nurses, or teachers.

"While burnout can affect anyone, at any age, in any industry, it's important to note that there are certain sectors and roles that are at increased risk, and purpose-driven work — that is work people love and feel passionately about — is one of them. According to a study published in the Journal of Personality, this type of labor can breed obsessive — versus harmonious — passion, which predicts an increase of conflict, and thus burnout. On The Mayo Clinic's list of burnout risks, two out of six are related to this mindset: "You identify so strongly with work that you lack balance between your work life and your personal life" and/or "You work in a helping profession".

Sometimes the easiest way to put an idea into context is to view it through the lens of your own work. As you might have guessed, I don't just have a passing interest in the future of work; I'm obsessed with it and spend much of my time researching and thinking about the ramifications of different approaches and models. Most of the time, of course, this is very fulfilling. However, there have been times of late that I've experienced some of the typical symptoms:

"1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; 2) increased mental distance from one's job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and 3) reduced professional efficacy."

In other words, the old adage that "if you do something you love, you'll never work a day in your life" isn’t always true.

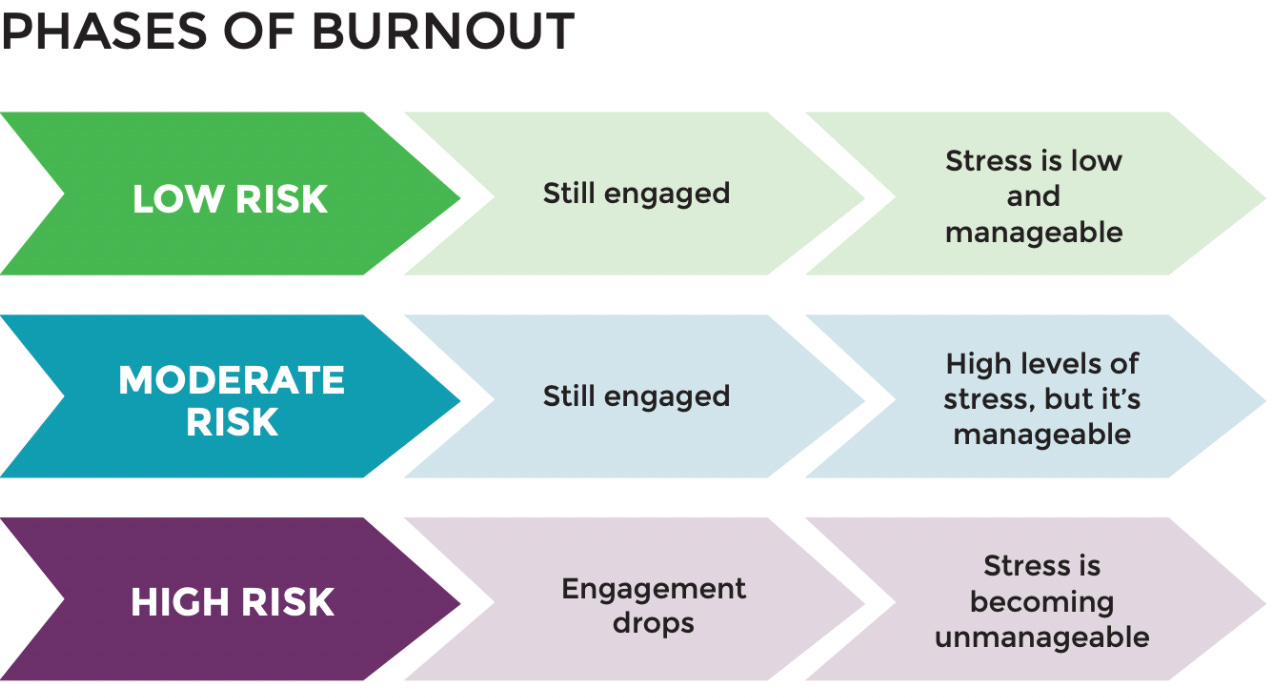

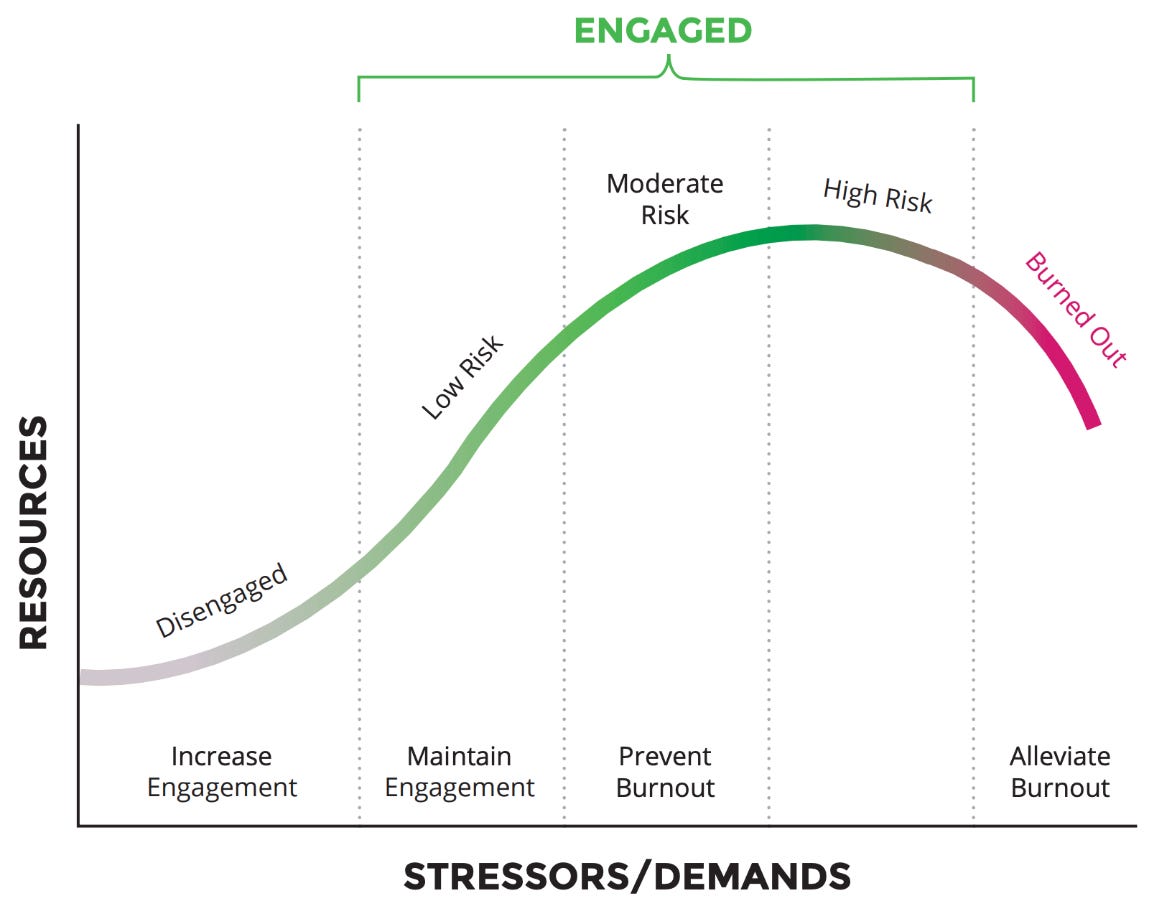

Burnout doesn’t necessarily mean breaking down. There’s a scale, and it’s important to recognise when you’re on it so you can take preemptive action. In my case, it took a conversation with an actual burnout expert to realise it, but this is absolutely where the people you work with (ideally, management) can step in, but also, your broader support network.

[Limeade]

Many of us are experiencing some degree of burnout, but stepping back to get some perspective and observing it ourselves can be tricky, which is why it requires an intervention from someone else. So, to take this one step further, you might look to build a 'challenge network', as Adam Grant has discussed in his excellent new book Think Again (although, for a more bite-sized explanation, you could listen to Grant on Tim Ferris's podcast).

While Grant discusses using this is as a way of challenging your thinking – which is a great idea, by the way – we could benefit from this in other aspects of our lives too. Not least, looking out for our wellbeing with some positively intended advice to slow down or take some time off.

Wellbeing can't be workload

Something Jen said during our chat really resonated with me. The idea of community at work has never been more critical, particularly for people used to congregating in offices. Research from Gallup has shown, for example, that having a best friend at work can significantly impact how engaged you are at work. Therefore, it makes sense that we attempt to create opportunities to interact with colleagues outside of typical Zoom meetings and digital comms. While well-intentioned, however, there were many cases last year where it went too far, and people began finding the requirement to be on 'Friday Zoom Cocktails' a massive pain in the arse rather than an enjoyable bookend to the week.

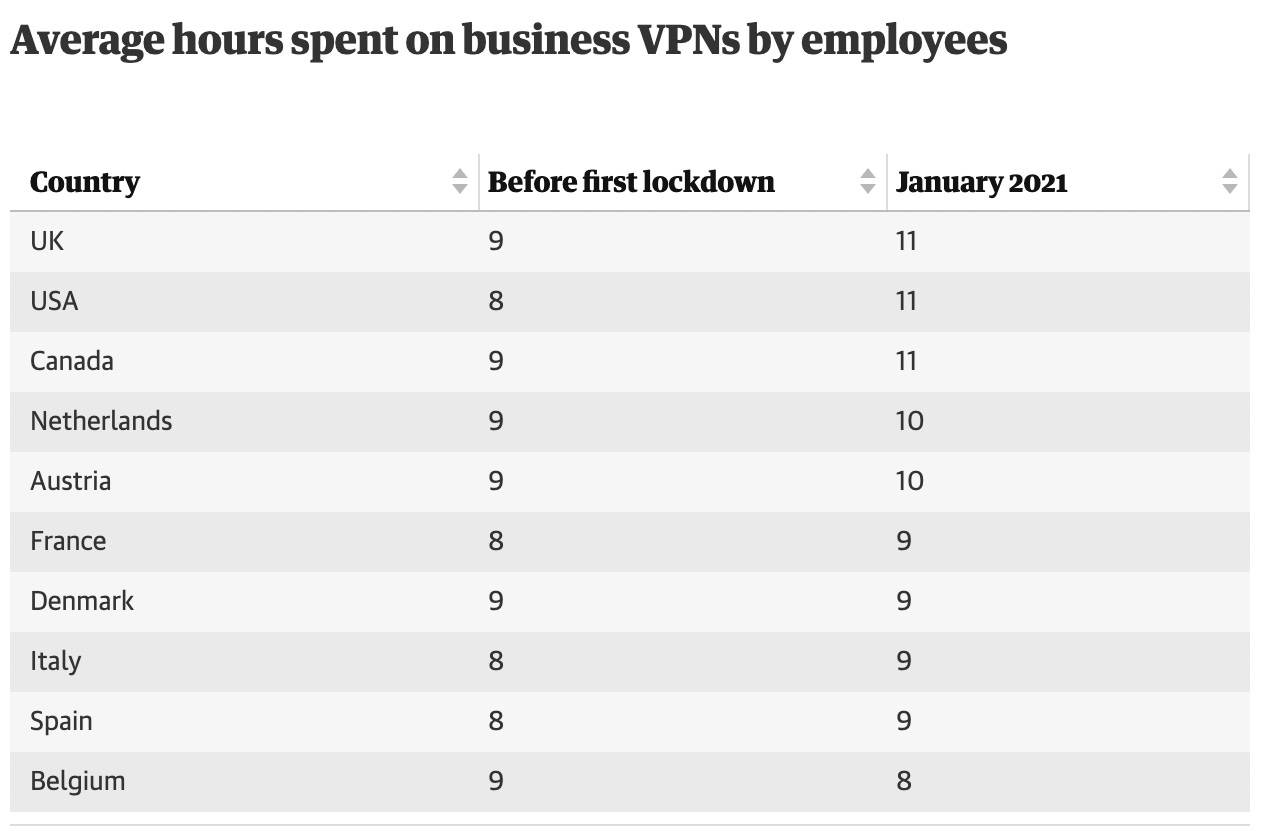

Likewise, free yoga or mindfulness sessions - while they're obviously fantastic ways to improve mental wellbeing and de-stress, they're not if you have to do this outside of 'work hours'. If your workday has been getting gradually longer, the last thing you want is your manager or HR rep maneuvring you into adding another hour to your day while you listen to Bob from Sales grunting his way through a Yoga Flow class.

[Guardian]

There's an easy answer here, and it isn't to halt all attempts to introduce positive habits into the workday – the point is it has to be part of a workday. In other words, an hour of yoga instead of an hour of meetings.

We have to draw boundaries, and there should be no expectations that the time should be 'made up' elsewhere.

Plus, let people choose what they do and when they do it - it's right there at number two in the six causes!

I've said it before, and I'll say it again; let's use this as a chance to change our understanding of what management is and upskill the people doing it. The idea of the 'flipped workplace' is that managers become more like facilitators and coaches. After all, elite sports coaches help their teams manage their lives and work and optimise physical and mental health because it allows them to perform better.

Remember that long before it gets so bad that you're unable to work, you go through a period in which you make poor decisions and when your mood and outlook can have adverse outcomes for teams and clients.

We're all now aware of the extent of burnout, so let's not just keep an eye out for the signs but create a culture that puts wellbeing front and centre.

Any Other Business:

If you’d like to read more about why it’s the fault of bosses that workers are so disengaged, check out this article by Francesca Gino and Dan Cable in the Wall Street Journal. According to the headline, the difference between employees who see the pandemic as an opportunity or a threat comes down to their mindset.

Podcast episode of the week has got to be Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and author of Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman, on the aforementioned Adam Grant’s Work/Life by TED. Kahneman explains how he finds joy in being wrong, outlines the steps required for better interviews and discusses how he approaches decision-making.

Founder and former CEO of Reward Gateway, Glenn Elliot, will be joining me on the next series of Take My Advice (I’m Not Using It). He’s now Entrepreneur in Residence of the PE firm, Tenzing, and this week wrote an excellent piece this week on employee onboarding. Having grown a global business over the past decade with employees based in multiple offices, Glenn’s an old hand and offers up some useful, practical tips for anyone who’s struggled with virtual onboarding in the last twelve months.

I’ve written a fair bit about the 4-day working week, but there are plenty of businesses experimenting with shorter working days, including Tower, ‘a holistic beach-lifestyle company’. It sounds like the perfect business for it, to be honest, and their founder, Stephan Aarstol, offers an interesting take on how it’s worked for them in Fast Company.

Finally, we all recognise this problem - when to shut up. According to this article in Scientific American, “people literally don’t know when to shut up - or keep talking”.