Future Work/Life is my newsletter in which I explore ideas focused on the future of work and how to design legendary careers. If you find it interesting, please share it!

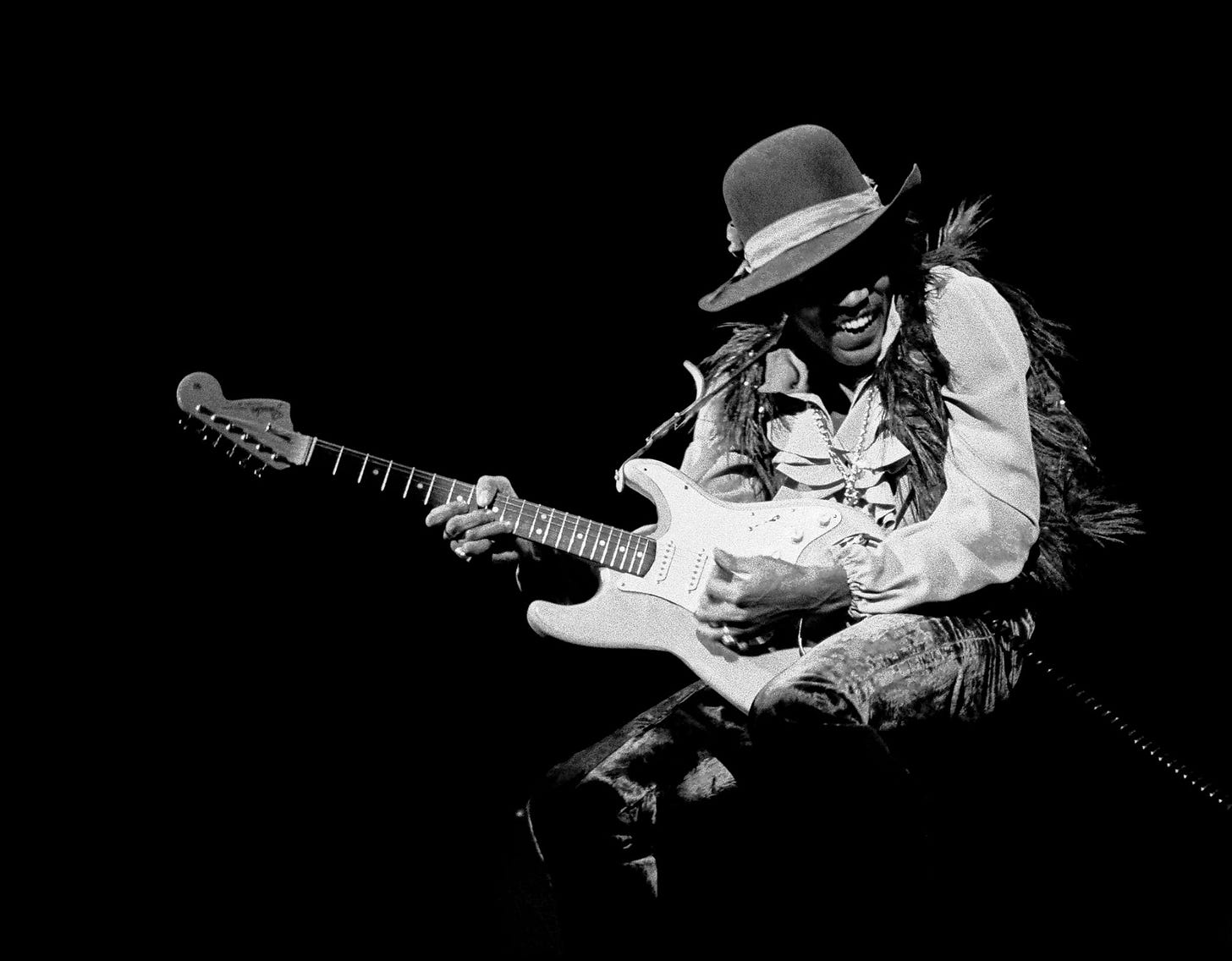

In the early 1960s, Little Richard was on a seemingly perpetual tour of the US and Europe, accompanied by his band and roadie, Jimmy James.

Touring rock’n’roll bands would crisscross their way over continents in that era, bumping into one another and getting to know the skills and expertise of the many rhythm sections and backing bands that kept the musical wheels in motion. Among them all, Jimmy was known as a solid guy who also happened to be able to play a bit of guitar. Nothing special, but good enough to eventually become Little Richard’s regular guitarist.

Fast forward a couple of years, and as was the norm, yet another new bit of kit was being touted by an equipment manufacturer to the touring bands: the Vox Wah Wah pedal promised to make you sound like a trombone.

For some, like Johnny Echols, guitarist of the iconic band Love, this was a pointless accessory. If Love wanted a trombone in their band, they’d find someone to play the real thing. He had no desire to look beyond what Vox said the pedal could do and rather than try it out to discover if it could add anything new and unexpected, he chucked it in the bin.

A year later, Echols and his bandmates heard a new guitar virtuoso was in town from the UK. They rushed to the Whisky a Go Go music venue in Los Angeles to see him play. Jimi Hendrix was as incredible as the stories promised. The band were amazed, but not because of his extraordinary talent. Instead, they realised three things:

1. The guy might be living in the UK, but he was actually American.

2. The American was making his guitar talk and scream through a Vox Wah Wah pedal.

3. Jimi Hendrix was, in fact, Jimmy James – roadie/jobbing guitarist from Little Richard’s band.

[Steve Banks]

Hendrix had taken this new technology and, unbound by the constraints of what it should do, he’d developed a whole new sound, unleashing new levels of creativity in guitar-playing and musical production that have inspired millions since.

The technology had elevated his guitar playing.

My point?

I’m not sure about you, but I’ve had a quick go with the various AI tools over the past year, and most of the results have not been good. The artwork I tried to create on DALL-E was atrocious. The articles I produced on ChaptGPT were dull, generic and full of unsubstantiated errors. The lack of any swift revelatory outcome left me quickly losing interest.

Is it because the tools are useless? Definitely not.

Is it because I’m incapable of using them? Probably not.

Am I going to do an Echols and metaphorically chuck it in the bin? Of course not.

Much like Echols and the Wah Wah pedal, I haven’t experienced a breakthrough because I haven’t invested any real effort in testing and learning how Chat GPT, DALL-E and the like can help me achieve specific aims. In my case, I can easily envisage how an AI chatbot could act as a digital researcher, creative muse or devil’s advocate. If I give it more time, I’m confident that when prompted intelligently, accessing its vast reservoirs of information will support my research, provide some alternative angles, and potentially trigger helpful thought experiments.

So far, though, like most people, I’m observing technological innovation from the sidelines, making it impossible to discover what’s possible.

Which is, of course, why I draw the Echols vs Hendrix analogy. Now, I’m not saying the tools are directly comparable – an electronic guitar pedal is very different from generative AI. But the principle applies. It was only through a willingness to experiment and craft a unique approach that Jimi created his sound.

I wonder what your ‘sound’ will be when you play with these emerging tools.

Yes, some may take to using these tools more quickly (and make money for their ability to do so), but ultimately, we’ll all have to master them. Prompting AI is likely to become a vital and required skill in the future of work and life. And given the recent news of Microsoft’s investment in ChatGPT creator OpenAI to power Microsoft products like the Bing search engine, this may happen sooner than you think.

Products enter the market and seem designed only for technically-minded folk, but eventually, they cross over into the mainstream. For example, consider the original search engines, smartphones and Zoom over the past two decades alone.

So, here's an opportunity to learn the skill before 99% of others and take advantage of being an early adopter to help power whatever project or idea you want to prioritise this year.

With that in mind, here are some of the most interesting ideas and tests I’ve seen former Future Work/Life podcast guests sharing over the past couple of months:

Azeem Azhar: "Using ChatGPT in the innovation process"

Dror Poleg: "AI and the Long Tail"

Hung Lee: "A series of interview questions for a CEO hiring a Head of Talent"

Justin Welsh: "Create Better Content, Faster, with ChatGPT"

Nicolas Cole: "How to write Atomic Essays using ChatGPT"

Plus, this is what Wharton Professor Ethan Mollick’s been up to: “The practical guide to using AI to do stuff”

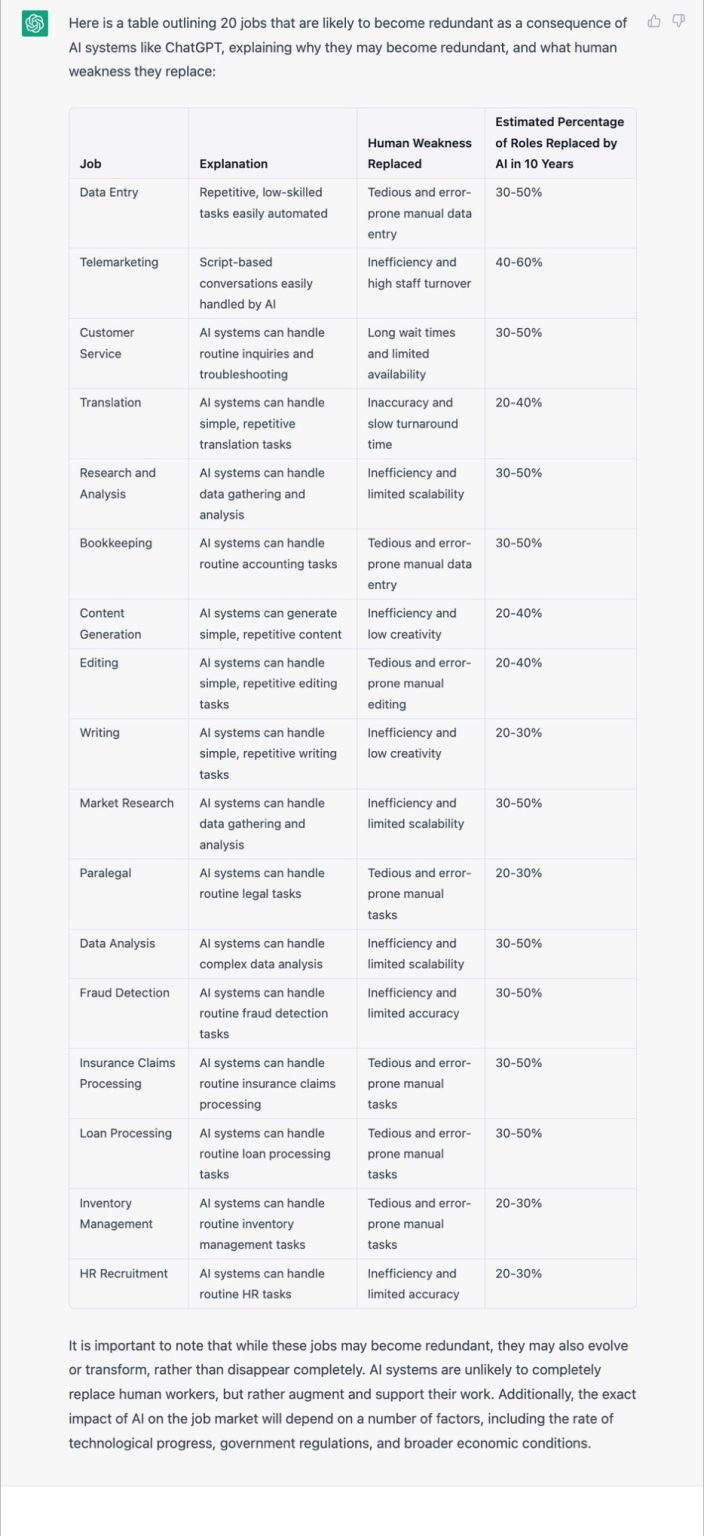

And here’s what ChatGPT itself has suggested are the jobs most at threat by its existence (thanks to Azeem for this prompt).

Thanks for reading and have a lovely weekend,

Ollie