I've always loved sport; any sport. When I was a child, my favourites were football and cricket. However, I was just as likely to watch (what were to my eyes) more obscure pursuits like cliff diving, lugeing, or kabaddi (all accessible to UK viewers in the early 90s via a magical programme on Channel 4 called Transworld Sport).

When the Olympics came around every four years, I was in dreamland; consumed for weeks by weightlifting, table tennis and modern pentathlon – who thought up a combination of running, swimming, riding a horse, shooting a pistol and sword fighting? Genius!

I also distinctly remember getting home from school in the summer every year and catching the end of the Tour de France coverage. Aside from that, up until a few years' ago cycling for me only meant the daily dicing with death on London's streets during my office commute. Recently, however, I've become fascinated with the sport, its traditions, and its peculiarities.

Why this sudden interest in cycling? Like many sports, it's only really when you dig below the surface that you start to appreciate both the tactics and physicality of the athletes. While some of the language and terminology still remains impenetrable to me, it's impossible not to admire the feats of human endurance and strength when you watch these people pedalling for hours on end, and up gradients of more than 20% (for reference, here's what that kind slope looks like…)

It also delivers moments of awe. Take Tao Geoghan Hart, for example, a local lad to us, who recently won the Giro D'Italia and is now the inspiration for my 8-year-old as he rides his bike around the local park. His story is, in many ways, what's notable about many professional cyclists since he was never expected to win the race - one of the sport's Grand Tours. Instead, he was there as a domestique for his team leader: expected to ride every day of a three-week race in support of someone else.

For me, this is what's most notable about professional cyclists, for whom the defining characteristic is not perhaps their physical attributes but their mentality. Not just the undoubted ability to push through even the most severe stresses and strains on their body but to measure their achievement in an entirely different context to most sportspeople.

They understand their role - their purpose - and it's not all about winning. It's about the collective. So much so, that some cyclists never win a single race.

I interviewed Cath Bishop for my new podcast, Take My Advice, last week. Cath is a three-time Olympic rower, winning a silver medal in Athens in 2004, as well a World title in 2003. She's also had a successful diplomatic career and is now the author of The Long Win: The Search For A Better Way To Succeed.

She explains that:

"The separation of 'performance' and 'results' is becoming second nature to most elite athletes. It doesn't mean that results aren't important, far from it, but it recognises that an athlete can develop. Results can never be guaranteed or controlled. They depend on external factors ranging from conditions to the weather, referees and umpires, not to mention your competitors. I know first-hand that it's a completely different experience to sit on the start-line of a race waiting to deliver your best performance than to sit there feeling that you have to win. Those two experiences are worlds apart, and the performances that follow usually are too."

Following what, by any measure, was a highly successful sporting life, but one that was, as a result of the inevitable ups and downs of competition, punctuated by periods of self-doubt and self-criticism, Cath began reframing her view on winning. She observed that our obsession with winning - whether in sport, business or life - holds us back and that we need new ways of measuring success.

Take education, for example. Sir Ken Robinson's TED talk, 'Do schools kill creativity?', is the most-watched of all time. Yet, we still seem to be sticking with methods of teaching and measurement of performance that make little allowance either for the individual characteristics of our children or the necessity that we prepare them for an uncertain and rapidly evolving future.

The same is true in higher education, which assumes that studying for a degree over a few years is the best and only route into potentially, a fifty-year career.

Thankfully, we're beginning to see innovation, particularly in tertiary education as, for example, technology businesses apply some of their big-idea thinking to personal development.

Google, for example, have an excellent track record in providing practical, vocational, training for people in the digital marketing industries. As of this summer, they're now creating courses for the most in-demand tech roles. They and other employers will consider this qualification as an equivalent to a university degree and, critically, instead of accumulating substantial student debts, the courses cost a fraction of the price.

Udacity, founded by former Google executive, Sebastian Thrun (who I mentioned back in FWL#4), offers another approach to learning, focusing again on high-value skills taught by industry specialists. They emphasise the value of chopping up learning into smaller chunks and considering it as a lifelong process.

I'm sure that Google and Udacity's courses will evolve rapidly as the market demands new types of skills in the future. At the same time, I also expect new types of monetisation options emerging - in digital education initially, but in traditional universities too over time.

As life expectancy increases and we work for significantly longer, not only is lifelong learning necessary, we may have to adapt to several careers over that time. In that case, competition for the right learning partner will grow.

To that end, why shouldn't learning institutions - whether Udacity, Harvard, or the University of the Arts in London - offer a life-time subscription, providing ongoing and ever-current education and accreditation, while also amortising the cost?

Among the many excellent insights in Cath Bishop's book, the simplicity of the '3 C" framework – clarity (of purpose), constant learning and connection (with others) - is the one that has stuck with me. As she neatly puts it:

"Working on the three C's requires proactive choices and deliberate action. When we open ourselves up to finding the 'why' in our lives, to mastery and connecting more deeply with others, it brings fun, mastery and meaning to what we do. Together, these areas can help us connect with ourselves and others around us and counteract the pull towards a narrow, limiting, short-term focus on winning at all costs."

I'm sure you'll agree this is the perfect moment to look beyond the short-term!

If you want to hear more from Cath, you can listen to our conversation when the podcast episode is released next Tuesday.

Have a lovely weekend,

Ollie

Any Other Business:

I was reminded of this fantastic David Ogilvy quote this week, which serves as a timely reminder that to come up with great ideas and make real break-throughs, whatever the challenge, you need to take some time to switch-off and relax.

“Big ideas come from the unconscious. This is true in art, in science, and in advertising. But your unconscious must be well informed, or your idea will be irrelevant. Stuff your conscious mind with information, then unhook your rational thought process.”

If you’re interested in data and analytics, I’m hosting an event this afternoon on Zoom. I’ll be joined by guests from BeIN Media, Comparethemarket.com, The Gym Group, and The National Basketball Association (NBA). You can sign up HERE.

Talking of education and technology, this podcast with Alison Baum and Cansu Deniz Bayrak is an interesting listen.

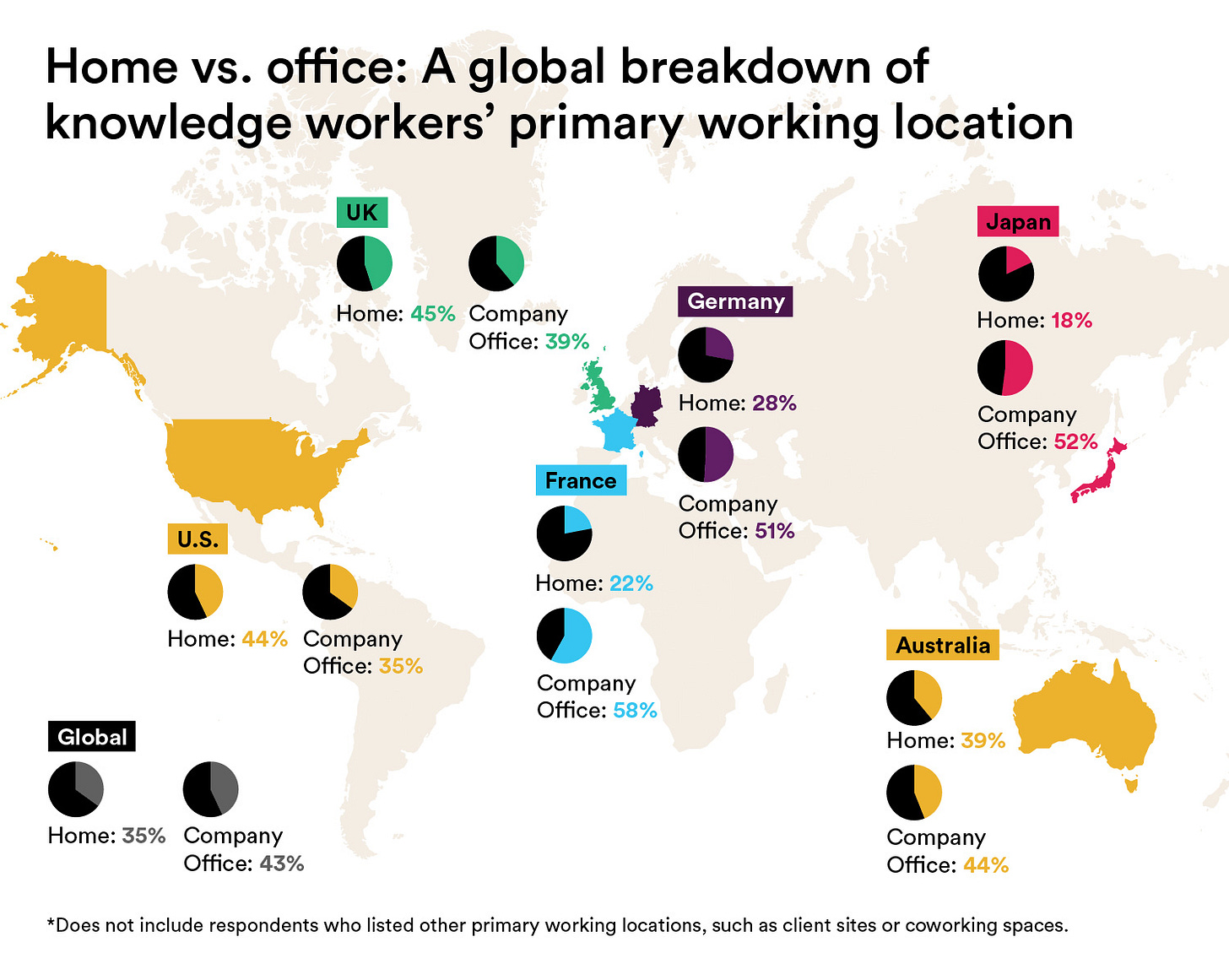

This is a comprehensive survey examining the future of work beyond Covid-19, from Slack. It’s long, so if you’re short of time, here are the best graphics: